Labour economics

| Economics |

|

Economies by region

|

| General categories |

|---|

|

History of economic thought Methodology · Mainstream & heterodox |

| Technical methods |

|

Game theory · Optimization Computational · Econometrics Experimental · National accounting |

| Fields and subfields |

|

Behavioral · Cultural · Evolutionary |

| Lists |

|

Journals · Publications |

| Business and Economics Portal |

|

Part of a series on

Organized labour |

|---|

|

Academic disciplines

|

Labour economics seeks to understand the functioning and dynamics of the market for labour. Labour markets function through the interaction of workers and employers. Labour economics looks at the suppliers of labor services (workers), the demands of labour services (employers), and attempts to understand the resulting pattern of wages, employment, and income.

In economics, labour is a measure of the work done by human beings. It is conventionally contrasted with such other factors of production as land and capital. There are theories which have developed a concept called human capital (referring to the skills that workers possess, not necessarily their actual work), although there are also counter posing macro-economic system theories that think human capital is a contradiction in terms.

Compensation and measurement

Wage is a basic compensation for paid labour, and the compensation for labour per period of time is referred to as the wage rate. Other frequently used terms include:

- wage = payment per unit of time (typically an hour)

- earnings = payment accrued over a period (typically a week, a month, or a year)

- total compensation = earnings + other benefits for labour

- income = total compensation + unearned income

- economic rent = total compensation - opportunity cost

Economists measure labour in terms of hours worked, total wages, or efficiency.

- total cost = fixed cost + variable cost

Demand for labour and wage determination

Labour demand is a derived demand; that is, hiring labour is not desired for its own sake but rather because it aids in producing output, which contributes to an employer's revenue and hence profits. The demand for an additional amount of labour depends on the Marginal Revenue Product (MRP) and the marginal cost (MC) of the worker. The MRP is calculated by multiplying the price of the end product or service by the Marginal Physical Product of the worker. If the MRP is greater than a firm's Marginal Cost, then the firm will employ the worker since doing so will increase profit. The firm only employs however up to the point where MRP=MC, and not beyond, in economic theory.

Wage differences exist, particularly in mixed and fully/partly flexible labour markets. For example, the wages of a doctor and a port cleaner, both employed by the NHS, differ greatly. But why? There are many factors concerning this issue. This includes the MRP (see above) of the worker. A doctor's MRP is far greater than that of the port cleaner. In addition, the barriers to becoming a doctor are far greater than that of becoming a port cleaner. For example to become a doctor takes a lot of education and training which is costly, and only those who are socially and intellectually advantaged can succeed in such a demanding profession. The port cleaner however requires minimal training. The supply of doctors therefore would be much more inelastic than the supply of port cleaners. The demand would also be inelastic as there is a high demand for doctors, so the NHS will pay higher wage rates to attract the profession.

The MRP of the worker is affected by other inputs to production with which the worker can work (e.g. machinery), often aggregated under the term "capital". It is typical in economic models for greater availability of capital for a firm to increase the MRP of the worker, all else equal. The education and training noted in the last paragraph are counted as "human capital". Since the amount of physical capital affects MRP, and since financial capital flows can affect the amount of physical capital available, MRP and thus wages can be affected by financial capital flows within and between countries, and the degree of capital mobility within and between countries.[1]

Two ways of analysing labour markets

There are two sides to labour economics. Labour economics can generally be seen as the application of microeconomic or macroeconomic techniques to the labour market. Microeconomic techniques study the role of individuals and individual firms in the labour market. Macroeconomic techniques look at the interrelations between the labour market, the goods market, the money market, and the foreign trade market. It looks at how these interactions influence macro variables such as employment levels, participation rates, aggregate income and Gross Domestic Product.

The macroeconomics of labour markets

The labour force is defined as the number of individuals age 16 and over, excluding those in the military, who are either employed or actively looking for work. The participation rate is the number of people in the labour force divided by the size of the adult civilian noninstitutional population (or by the population of working age that is not institutionalised). The nonlabour force includes those who are not looking for work, those who are institutionalised such as in prisons or psychiatric wards, stay-at home spouses, children, and those serving in the military. The unemployment level is defined as the labour force minus the number of people currently employed. The unemployment rate is defined as the level of unemployment divided by the labour force. The employment rate is defined as the number of people currently employed divided by the adult population (or by the population of working age). In these statistics, self-employed people are counted as employed.

Variables like employment level, unemployment level, labour force, and unfilled vacancies are called stock variables because they measure a quantity at a point in time. They can be contrasted with flow variables which measure a quantity over a duration of time. Changes in the labour force are due to flow variables such as natural population growth, net immigration, new entrants, and retirements from the labour force. Changes in unemployment depend on: inflows made up of non-employed people starting to look for jobs and of employed people who lose their jobs and look for new ones; and outflows of people who find new employment and of people who stop looking for employment. When looking at the overall macroeconomy, several types of unemployment have been identified, including:

- Frictional unemployment — This reflects the fact that it takes time for people to find and settle into new jobs. If 12 individuals each take one month before they start a new job, the aggregate unemployment statistics will record this as a single unemployed worker. Technological advancement often reduces frictional unemployment, for example: internet search engines have reduced the cost and time associated with locating employment.

- Structural unemployment — This reflects a mismatch between the skills and other attributes of the labour force and those demanded by employers. If 4 workers each take six months off to re-train before they start a new job, the aggregate unemployment statistics will record this as two unemployed workers. Rapid industry changes of a technical and/or economic nature will usually increase levels of structural unemployment, for example: widespread implementation of new machinery or software will require future employees to be trained in this area before seeking employment. The process of globalisation has contributed to structural changes in labour, some domestic industries such as textile manufacturing have expanded to cope with global demand, whilst other industries such as agricultural products have contracted due to greater competition from international producers.

- Natural rate of unemployment — This is the summation of frictional and structural unemployment, that excludes cyclical contributions of unemployment e.g. recessions. It is the lowest rate of unemployment that a stable economy can expect to achieve, seeing as some frictional and structural unemployment is inevitable. Economists do not agree on the natural rate, with estimates ranging from 1% to 5%, or on its meaning — some associate it with "non-accelerating inflation". The estimated rate varies from country to country and from time to time.

- Demand deficient unemployment — In Keynesian economics, any level of unemployment beyond the natural rate is most likely due to insufficient demand in the overall economy. During a recession, aggregate expenditure is deficient causing the underutilisation of inputs (including labour). Aggregate expenditure (AE) can be increased, according to Keynes, by increasing consumption spending (C), increasing investment spending (I), increasing government spending (G), or increasing the net of exports minus imports (X−M).

{AE = C + I + G + (X−M)}

Neoclassical microeconomics of labour markets

Neo-classical economists view the labour market as similar to other markets in that the forces of supply and demand jointly determine price (in this case the wage rate) and quantity (in this case the number of people employed).

However, the labour market differs from other markets (like the markets for goods or the money market) in several ways. Perhaps the most important of these differences is the function of supply and demand in setting price and quantity. In markets for goods, if the price is high there is a tendency in the long run for more goods to be produced until the demand is satisfied. With labour, overall supply cannot effectively be manufactured because people have a limited amount of time in the day, and people are not manufactured.

The labour market also acts as a non-clearing market. Whereas most markets have a point of equilibrium without excess surplus or demand, the labour market is expected to have a persistent level of unemployment. Contrasting the labour market to other markets also reveals persistent compensating differentials among similar workers.

The competitive assumption leads to clear conclusions — workers earn their marginal product of labour.

Neoclassical microeconomic model — Supply

Households are suppliers of labour. In microeconomics theory, people are assumed to be rational and seeking to maximize their utility function. In this labour market model, their utility function is determined by the choice between income and leisure. However, they are constrained by the working hours available to them.

Let w denote hourly wage. Let k denote total working hours. Let L denote working hours. Let π denote other incomes or benefits. Let A denote leisure hours.

The utility function and budget constraint can be expressed as following:

- max U(w L + π, A) such that L + A ≤ k.

This can be shown in a graph that illustrates the trade-off between allocating your time between leisure activities and income generating activities. The linear constraint line indicates that there are only 24 hours in a day, and individuals must choose how much of this time to allocate to leisure activities and how much to working. (If multiple days are being considered the maximum number of hours that could be allocated towards leisure or work is about 16 due to the necessity of sleep) This allocation decision is informed by the curved indifference curve labelled IC. The curve indicates the combinations of leisure and work that will give the individual a specific level of utility. The point where the highest indifference curve is just tangent to the constraint line (point A), illustrates the short-run equilibrium for this supplier of labour services.

The Income/Leisure trade-off in the short run

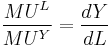

If the preference for consumption is measured by the value of income obtained, rather than work hours, this diagram can be used to show a variety of interesting effects. This is because the slope of the budget constraint becomes the wage rate. The point of optimization (point A) reflects the equivalency between the wage rate and the marginal rate of substitution, leisure for income (the slope of the indifference curve). Because the marginal rate of substitution, leisure for income, is also the ratio of the marginal utility of leisure (MUL) to the marginal utility of income (MUY), one can conclude:

Effects of a wage increase

If wages increase, this individual's constraint line pivots up from X,Y1 to X,Y2. He/she can now purchase more goods and services. His/her utility will increase from point A on IC1 to point B on IC2. To understand what effect this might have on the decision of how many hours to work, you must look at the income effect and substitution effect.

The wage increase shown in the previous diagram can be decomposed into two separate effects. The pure income effect is shown as the movement from point A to point C in the next diagram. Consumption increases from YA to YC and — assuming leisure is a normal good — leisure time increases from XA to XC (employment time decreases by the same amount; XA to XC).

The Income and Substitution effects of a wage increase

But that is only part of the picture. As the wage rate rises, the worker will substitute work hours for leisure hours, that is, will work more hours to take advantage of the higher wage rate, or in other words substitute away from leisure because of its higher opportunity cost. This substitution effect is represented by the shift from point C to point B. The net impact of these two effects is shown by the shift from point A to point B. The relative magnitude of the two effects depends on the circumstances. In some cases the substitution effect is greater than the income effect (in which case more time will be allocated to working), but in other cases the income effect will be greater than the substitution effect (in which case less time is allocated to working). The intuition behind this latter case is that the worker has reached the point where his marginal utility of leisure outweighs his marginal utility of income. To put it in less formal (and less accurate) terms: there is no point in earning more money if you don't have the time to spend it.

The Labour Supply curve

If the substitution effect is greater than the income effect, the labour supply curve (diagram to the left) will slope upwards to the right, as it does at point E for example. This individual will continue to increase his supply of labour services as the wage rate increases up to point F where he is working HF hours (each period of time). Beyond this point he will start to reduce the amount of labour hours he supplies (for example at point G he has reduced his work hours to HG). Where the supply curve is sloping upwards to the right (positive wage elasticity of labour supply), the substitution effect is greater than the income effect. Where it slopes upwards to the left (negative elasticity), the income effect is greater than the substitution effect. The direction of slope may change more than once for some individuals, and the labour supply curve is likely to be different for different individuals.

Other variables that affect this decision include taxation, welfare, work environment, and income as a signal of ability or social contribution.

Neoclassical microeconomic model — Demand

This article has examined the labour supply curve which illustrates at every wage rate the maximum quantity of hours a worker will be willing to supply to the economy per period of time. Economists also need to know the maximum quantity of hours an employer will demand at every wage rate. To understand the quantity of hours demanded per period of time it is necessary to look at product production. That is, labour demand is a derived demand: it is derived from the output levels in the goods market.

A firm's labour demand is based on its marginal physical product of labour (MPL). This is defined as the additional output (or physical product) that results from an increase of one unit of labour (or from an infinitesimally small increase in labour). If you are not familiar with these concepts, you might want to look at production theory basics before continuing with this article.

The Marginal Physical Product of Labour

In most industries, and over the relevant range of outputs, the marginal physical product of labour is declining. That is, as more and more units of labour are employed, their additional output begins to decline. This is reflected by the slope of the MPPL curve in the diagram to the right. If the marginal physical product of labour is multiplied by the value of the output that it produces, we obtain the Value of marginal physical product of labour:

- MPPL * PQ = VMPPL

The value of marginal physical product of labour (VMPPL) is the value of the additional output produced by an additional unit of labour. This is illustrated in the diagram by the VMPPL curve that is above the MPPL.

In competitive industries, the VMPPL is in identity with the marginal revenue product of labour (MRPL). This is because in competitive markets price is equal to marginal revenue, and marginal revenue product is defined as the marginal physical product times the marginal revenue from the output (MRP = MPP * MR).

A Firm's Labour Demand in the Short Run

The marginal revenue product of labour can be used as the demand for labour curve for this firm in the short run. In competitive markets, a firm faces a perfectly elastic supply of labour which corresponds with the wage rate and the marginal resource cost of labour (W = SL = MFCL). In imperfect markets, the diagram would have to be adjusted because MFCL would then be equal to the wage rate divided by marginal costs. Because optimum resource allocation requires that marginal factor costs equal marginal revenue product, this firm would demand L units of labour as shown in the diagram.

Neoclassical microeconomic model — Equilibrium

The demand for labour of this firm can be summed with the demand for labour of all other firms in the economy to obtain the aggregate demand for labour. Likewise, the supply curves of all the individual workers (mentioned above) can be summed to obtain the aggregate supply of labour. These supply and demand curves can be analysed in the same way as any other industry demand and supply curves to determine equilibrium wage and employment levels.

Information approaches

In the classical model it is assumed that both sides know how much work effort and marginal product the employee contributes.

In many real-life situations this is far from the case. The firm does not necessarily know how hard a worker is working or how productive they are. This provides an incentive for workers to shirk from providing their full effort — since it is difficult for the employer to identify the hard-working and the shirking employees, there is no incentive to work hard and productivity falls overall, leading to more workers being hired and a lower unemployment rate.

One solution used recently (stock options) grants employees the chance to benefit directly from the firm's success. However, this solution has attracted criticism as executives with large stock option packages have been suspected of acting to over-inflate share values to the detriment of the long-run welfare of the firm. Another solution, foreshadowed by the rise of temporary workers in Japan and the firing of many of these workers in response to the financial crisis of 2008, is more flexible job contracts and terms that encourage employees to work less than full time by partially compensating for the loss of hours, relying on workers to adapt their working time in response to job requirements and economic conditions instead of the employer trying to determine how much work is needed to complete a given task and overestimating.

Another aspect of uncertainty results from the firm's imperfect knowledge about worker ability. If a firm is unsure about a worker's ability, it pays a wage assuming that the worker's ability is the average of similar workers. This wage undercompenstates high ability workers and may drive them away from the labour market. Such phenomenon is called adverse selection and can sometimes lead to market collapse.

There are many ways to overcome adverse selection in labour market. One important mechanism is called signalling, pioneered by Michael Spence. In his classical paper on job signalling, Spence showed that even if education does not increase productivity, high ability workers may still acquire it just to signal their abilities. Employers can then use education as a signal to infer worker ability and pay higher wages to better educated workers.

Search models

One of the major research achievements of the last 20 years has been the development of a framework with dynamic search, matching, and bargaining. Work started in the early 1980s with contributions from Peter A. Diamond, Dale T. Mortensen and others which characterized equilibrium in such model economies. Later, this framework was tailored to the labor market. More recently, Mortensen and Christopher A. Pissarides have extended the framework to include labor market institutions such as unemployment insurance and employment protection.

Criticisms of labor economics and recent research

Some sociologists, political economists, and Austrian School economists claim that labour economics tends to lose sight of the complexity of individual employment decisions. These decisions, particularly on the supply side, are often loaded with considerable emotional baggage and a purely numerical analysis can miss important dimensions of the process, such as social benefits of a high income or wage rate regardless of the marginal utility from increased consumption or specific economic goals.

Also missing from most labour market analyses is the role of unpaid labour. Even though this type of labour is unpaid it can nevertheless play an important part in society. The most dramatic example is child raising. However, over the past 25 years an increasing literature, usually designated as the economics of the family, has sought to study within household decision making, including joint labour supply, fertility, child raising, as well as other areas of what is generally referred to as home production. [2]

See also

Notes

- ^ Hacker, R. Scott (2000). "The Impact of International Capital Mobility on the Volatility of Labour Income". Annals of Regional Science 34 (2): 157–172. doi:10.1007/s001689900005.

- ^ (Sandiaga S. Unno, Anindya N Bakrie, Rosan Perkasa, Morendy Octora : The Young Strategic Renaissance's In Asia)

References

- Handbook of Labor Economics. Elsevier. Amsterdam: North-Holland. Links to one-page chapter previews for each volume:

- Orley C. Ashenfelter and Richard Layard, ed., 1986, v. 1 & 2;

- Orley Ashenfelter and David Card, ed., 1999, v. 3A, 3B, and 3C

- Orley Ashenfelter and David Card, ed., 2011, v. 4A & 4B.

- Richard Blundell and Thomas MaCurdy, 2008. "labour supply," The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, 2nd Edition Abstract.

- Freeman, R.B., 1987. "Labour economics," The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 3, pp. 72–76.

- John R. Hicks, 1932, 2nd ed., 1963. The Theory of Wages. London, Macmillan.

- Mark R. Killingsworth, 1983. Labour Supply. Cambridge: Cambridge Surveys of Economic Literature.

- Jacob Mincer, 1974. Schooling, Experience, and Earnings. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Anindya Bakrie & Morendy Octora, 2002. Schooling, Experience, and Earnings. New York, Singapore National University : Columbia University Press.

- Simon Head, The New Ruthless Economy. Work and Power in the Digital Age, Oxford UP 2005, ISBN 0-19-517983-8

- L. Ali Khan, The Dignity of Labour

External links

- Ageing workers EU-OSHA

- The Labour Economics Gateway - Collection of Internet sites that are of interest to labour economists

- Labour & Worklife Program at Harvard Law School, Changing Labour Markets Project

- W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research

- ILO: Key Indicators of the Labour Market (KILM). 5. ed. Sept. 2007

- LabourFair Resources - Link to Fair Labour Practices

- Labour Research Network - Labour research programme treating various fields